What is the field of microelectronics and why is it so important?

In this Q&A, SLAC experts discuss how microelectronic devices impact our lives, the breakthroughs needed for future technologies and how researchers at the lab are pursuing them.

By Carol Tseng

When we pick up our cell phones to make a call or search the internet, small – approximately 20,000 times thinner than a human hair – but powerful technology is working behind the scenes. Microelectronic devices enable a wide range of daily tasks from sending text messages to running cutting-edge instruments at hospitals and computing centers.

To learn more about these devices, we sat down with two microelectronics experts from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: Paul McIntyre, associate lab director for the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource Directorate and professor of photon science, and Angelo Dragone, deputy associate lab director for the Technology Innovation Directorate and professor of photon science. They discuss the current state of microelectronics and how SLAC’s leadership in materials science, X-ray science, detectors and developing state-of-the-art instrumentation will help drive the future of this field.

What is the field of microelectronics?

McIntyre: I think of microelectronics as an evolving set of technologies used for information processing, retrieval and storage, as well as connecting information systems to the physical world around us. Within that field sits two levels: the software level – computing applications that interact with microelectronics devices and decide how data will be manipulated and stored – and the hardware level – physical circuitry that allows these to happen.

Now, within that complex circuitry are many functional layers composed of many devices and wires. As we delve deeper and travel down the layers to the lower levels of this so-called microelectronics stack, we find individual devices and even atomic scale features that are fabricated to give the necessary functions. It’s quite a complex assembly of different component pieces and materials. Many are doing simple tasks, but they are happening at the same time. In the upper levels of this stack, lots of data shuffle around.

Dragone: Another way of thinking about microelectronics is in the combination of the terms: "electronics," a field that uses electrical signals to acquire or compute the data Paul refers to, and “micro,” integrating those signals in a very compact way.

Why is this field important for society?

McIntyre: The way we work and live nowadays is intimately connected to using microelectronics devices. These devices find many uses in health care, for instance, in imaging systems and increasingly in robotics for surgery. Recording medical data and understanding what it means also requires a lot of computation. We are increasingly able to use simulations to understand biological processes at the level of how disease progresses in human beings or how to predict the kinds of molecules that will be most effective as therapies or as vaccines for preventing the spread of disease.

Everybody now carries in their pocket a device that can access most of the knowledge humanity has collected throughout history. That didn't exist 25 years ago. But the continuous miniaturization of microelectronics, while making it more powerful, made this possible. We could fit components that used to be in a computer the size of a room into a much more powerful device that fits in your pocket and comes with an amazing digital camera. The societal impact of microelectronics is profound and transformational and has totally changed the way people live.

What are the challenges around microelectronics?

McIntyre: There are several challenges. Until recently, the primary way we have achieved increased functionality and reduced cost in microelectronics has been through making everything smaller and fitting more on a square inch or centimeter.

The energy utilization of microelectronic hardware has become increasingly significant. The extent to which electrical power is devoted to computation or keeping equipment cool enough to do computation is growing too rapidly. The Department of Energy funds a lot of great science and technology development that could be impactful here and directly ties into the energy economy of the U.S. and the world.

Dragone: Shrinking device dimensions, the traditional knob to reduce power consumption, has slowed down quite a bit. With more data from more devices to process, we have to move data faster within the chips. With data transfer becoming a bottleneck, how do we keep the pace of innovation in creating new microelectronic technologies and controlling energy consumption of the devices?

McIntyre: There's also the issue of being able to efficiently move data between individual pieces of hardware and the cloud or combinations of distributed systems. We have a significant need to develop new approaches for efficiently moving data that are scalable and done in an economic, secure and efficient way.

What are some aspects that SLAC is addressing?

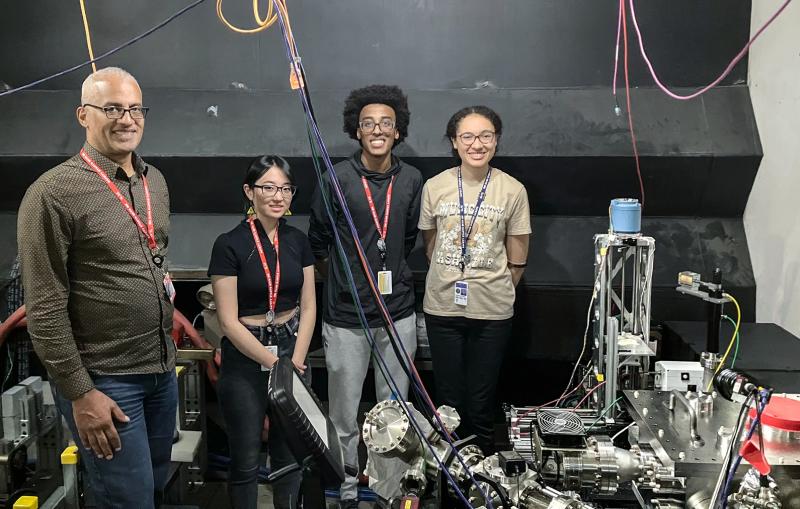

Dragone: We're working on multiple fronts. For instance, Paul has been working for many years in microelectronics technology at the materials level. New materials can allow us to build higher-performing transistors, both in terms of their size and the way they interconnect. Novel ways to interconnect can make communication faster. These new devices need to reliably integrate into commercial processes, and then we can start building circuits that can leverage these novel device properties.

We are also working on new kinds of circuit and sensor architectures for applications that allow us to interface with the world. It’s important to understand how to integrate and perform new computation methods in hardware. Instead of designing hardware and software in sequence as we do now, we have to design the computation algorithms in a way that can operate on the hardware while at the same time designing the hardware for that specific algorithm. This is the idea of co-design.

McIntyre: As an accelerator laboratory, our accelerators allow us to operate major scientific user facilities. There is interest in accelerators for potential approaches for new kinds of device fabrication, for example, as a new source for lithographic patterning, a way to create the very small features needed.

Building on our expertise and accelerator capabilities, materials characterization techniques and sensing systems, we can develop new kinds of metrology for studying the dimensions, the physical layout and the composition of microelectronic circuits at various stages in their fabrication. Researchers from the microelectronics industry use our tools to study new materials and new types of devices.

How will other new technologies, such as AI, come into play?

McIntyre: We are interested in automating experimentation at our facilities so researchers get results more quickly. Some of the automation principles and our use of AI and scientific computing to guide how we design experiments could also be important in manufacturing. We are looking into digital twins to run complex experiments at a user facility and potentially to inform how a new manufacturing process might work.

There is also substantial overlap between microelectronics and quantum information science and technology. Some of the microelectronics research over the years – developing the ability to stack functionality, making devices with tremendous fidelity from one to another and controlling dimensions at the atomic scale – can be leveraged in quantum devices. There's also the issue of how to interface quantum computing and quantum technologies with classical microelectronics.

Dragone: In many cases, these quantum devices operate at very low temperatures. We have experience in designing circuits that operate in extreme environments, for example, down to 4 kelvin, which can be used for interfacing quantum devices to classical computer devices.

McIntyre: I look at this interfacing as a potential growth area for the lab and its partners.

Microelectronics research at SLAC is funded by the DOE Office of Science Microelectronics Science Research Centers. SLAC leads the Enabling Science for Transformative Energy-Efficient Microelectronics (ESTEEM) and Adaptive Ultra-Fast Energy-Efficient Intelligent Sensing Technologies (AUREIS) projects for the Microelectronics Energy Efficiency Research Center for Advanced Technologies (MEERCAT) Center.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.